The UC San Diego NAFLD Research Center specializes in noninvasive imaging methods for diagnosing and monitoring the disease.

UC San Diego scientists find type 2 diabetes patients show a high prevalence of advanced liver disease, inspiring updates to the national screening guidelines

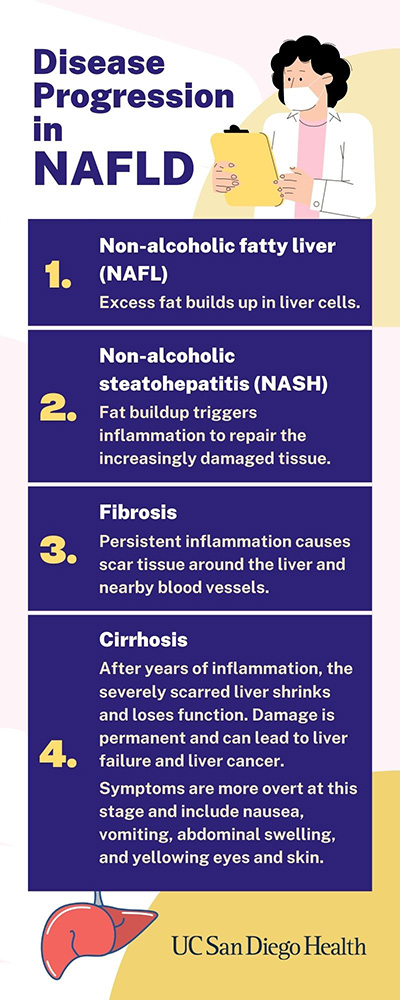

About 1 in 10 Americans have diabetes, with approximately 95% of cases being adult-onset or type 2 diabetes. But blood sugar is not the only thing diabetes patients should be concerned about. Having type 2 diabetes also puts you at a higher risk for many other diseases, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).  NAFLD is caused by a buildup of fat in the liver and can initially be managed with a healthy diet and exercise. But without early screening and treatment, NAFLD can quickly become a silent killer. By the time patients notice any symptoms, the disease has already progressed into the late stages of fibrosis or cirrhosis, in which severe liver scarring has done permanent damage to the organ’s function.

NAFLD is caused by a buildup of fat in the liver and can initially be managed with a healthy diet and exercise. But without early screening and treatment, NAFLD can quickly become a silent killer. By the time patients notice any symptoms, the disease has already progressed into the late stages of fibrosis or cirrhosis, in which severe liver scarring has done permanent damage to the organ’s function.

Physicians have long been aware of the general association between type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, but less is known about the exact prevalence of fibrosis and cirrhosis in these patients. In fact, previous guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) did not recommend any screening for fibrosis or cirrhosis in type 2 diabetes patients, because the data to support their association had not yet been collected.

But all this has changed thanks to a recent study led by Rohit Loomba, MD, gastroenterologist and professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine. The research team completed the first large-scale prospective study to quantify the prevalence of advanced NAFLD in type 2 diabetes patients.

The study recruited patients aged 50 or older who were visiting their primary care or endocrinology clinics for standard appointments but were not receiving any treatments for their liver health at the time. To ensure the highest accuracy of results, the researchers performed all diagnoses using state-of-the-art noninvasive imaging tools developed and validated at UC San Diego Health, as opposed to traditional measures such as painful liver biopsies or less conclusive blood tests.

Of the 501 type 2 diabetes patients they screened, 65% had NAFLD, 14% showed advanced fibrosis, 6% had cirrhosis and two patients had already developed liver cancer.

“We had a hunch that liver disease was common in diabetes, but to find out that 1 in 7 patients coming in for their standard appointments were silently suffering with advanced liver problems is a major concern,” said Loomba.

All patients were able to receive follow-up treatment through the clinical research program, but the findings still made a major impact on Loomba and his colleagues.

“I wish we had the chance to diagnose these patients five years ago so we could have intervened at earlier stages of the disease,” said Loomba. “Those two patients who developed liver cancer – I wish I could have prevented that.”

The team is now working to expand the clinical program across San Diego, and advocate for updates to the national screening guidelines. After personally presenting the data to the AASLD, Loomba has co-authored the latest set of clinical guidelines, to be released in the coming months, which include several major changes based, in part, on the work done at UC San Diego.

“We are working towards a future where all type 2 diabetes patients have access to early screening and treatment for liver disease, and these new screening guidelines will be a major step forward.”

— Nicole Mlynaryk