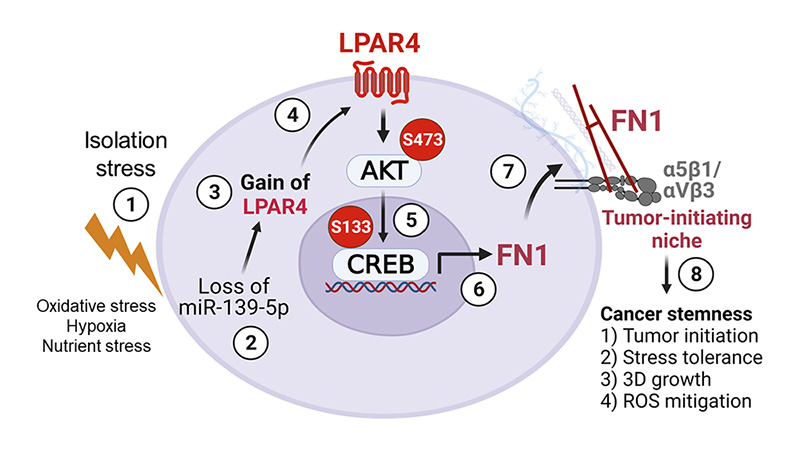

When a tumor-initiating cell experiences isolation stress, it begins expressing a membrane receptor called LPAR4. This leads the cell to produce a new extracellular matrix full of a protein called fibronectin (FN1), which keeps the cell safe and signals other cells to join. UC San Diego Health Sciences

When cancer cells first form, they become separated from the other cells around them, which starves them of critical oxygen and nutrients. Most cells do not survive this isolation stress, but a special population called tumor-initiating cells can. These stress-tolerant cells play a major role in the formation, recurrence and metastatic spread of tumors, but until recently, scientists didn’t know what made these cells so resilient.

In a new study published in the journal Nature Cell Biology, researchers at UC San Diego School of Medicine discovered a molecular pathway that allows tumor-initiating cells in the pancreas to create their own tumor-promoting microenvironment. Like cacti in a desert, they can adapt to the harsh conditions and set the scene for further tumor progression.

Led by David Cheresh, PhD, Distinguished Professor and vice chair of the Department of Pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and member of the UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center, the research team is now looking for drugs that can target this pathway.

Such therapeutics could be especially beneficial in:

- Preventing tumor formation in patients with pre-existing conditions that put them at a higher risk of developing cancer.

- Blocking tumor initiation in other parts of the body in patients with cancers that are likely to spread.

- Combatting drug resistance, as many standard cancer drugs work by putting the tumor under stress, which can trigger the appearance of new tumor-initiating cells.

Cheresh suggests that new drugs targeting tumor-initiating cells could be combined with other chemotherapeutics to better fight the progression and spread of cancer. The issue is they may not do much to the size of existing tumors, which is what early stages of clinical trials are often focused on.

“Most trials want to see if the drug is shrinking the tumor, but that’s not the only readout of disease progression we need to be concerned about,” said Cheresh. “At the end of the day, what really matters is survival — does a patient live longer with this therapy? Adding drugs that target tumor-initiating cells may be an important piece of that puzzle.”

Cheresh and colleagues will start a clinical trial of their first drug candidate this spring, and another is currently in pre-clinical tests.

“Now that we’ve uncovered this molecular pathway, we have something to sink our teeth into,” said Cheresh, “so the next step is to look at all the ways we can attack it and find which strategy works best.”

— Nicole Mlynaryk